Penguins “Cheat” to Stay Warm in Icy Waters

Many penguin species love cold environments, and even those that live in tropical latitudes often feed in very cold currents offshore. This presents a special challenge for small species. Theoretically, an endothermic (“warm-blooded”) animal needs to be about 7kg or larger to survive in cold water without some type of special heat retention mechanism. This is because volume increases faster than surface area as animals get larger, leading to slower heat transfer in larger animals and faster heat transfer in smaller animals. In theory at sizes below 7kg, the rate of heat loss to the surrounding cold water becomes too great and the animal will enter hypothermia. The smallest penguin alive today, the Little Blue Penguin (Eudyptula minor) is only about 1kg.

So how do these penguins survive? Regional heterothermy is a strategy in which an animal allows some parts of the body to cool down in order to preserve heat for the core. For penguins, this means letting the flippers cool down and keeping the brain and vital organs warm. As a means of propulsion, the penguin flipper is a marvel of evolution, perfectly suited for underwater “flight”. However, it is also a terrible heat sink. The flattened wing bones and tightly attached skin and feathers give the flipper a very high surface area to volume ratio, which means it will shed heat to surrounding air or water at a high rate. Immersed in icy water, a penguin-shaped object would cool fairly rapidly.

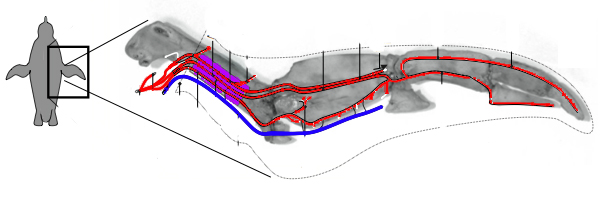

Penguins have a trick to keep this from happening. Blood vessels of the wing in penguins form a “rete mirabile”, a plexus of arteries and veins. This term means wonderful net in Latin, and it is indeed a wondrous evolutionary novelty. Arteries carry oxygenated blood from the heart of the penguin to the extremities, and veins return the de-oxygenated blood back again. In cold water, the blood from the arteries is hot, but the blood returning from the tips of the flippers and toes can be quite cold. As the normal arteries of the penguin blood vessel system run onto the flipper, they split into multiple parallel branches called a plexus. Each branch is closely aligned with at least two veins. The heat from the blood in the arteries warms the returning blood in the veins, raising the blood temperature before it returns to the heart. At the same time, the blood heading towards the flipper in the arteries is cooled, resulting in the flipper temperature dropping. This can lead to an impressive difference of up to 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) between the core temperature and wingtip temperature of penguins. The vital organs remain toasty, while the flippers dip towards freezing.

Schematic illustration of the rete in a Little Blue penguin, modified with permission from Thomas and Fordyce (2008). Arteries are shown in red and veins in blue, superimposed on a photo of the bones of the flipper. At the purple rectangle, each artery is associated with at least two smaller veins, forming the rete.

Recently Dr. Daniel Thomas and Dr. R. Ewan Fordyce studied this system in Little Blue Penguins (don’t worry, no penguins were hurt – only dead specimens found on beaches were dissected) and compared the number of arteries in the rete from different living species. They found that penguins from colder areas like Antarctica have more arteries than those from warmer environments. This would make sense in that a more sophisticated rete may be necessary in more extreme conditions. Alternatively, the number of vessels may correlate to size, as the species that lives in the most extreme environment, the Emperor Penguin, is also the largest.

This is another interesting example of just how specialized penguins are for life in extreme marine environments. The smallest species “cheat” to get in under the normal limits of viable body size for marine endotherms. While their very specialized feathers and flipper-like wings are easily visible, some of the cool characteristics that make penguins “work” lie beneath the surface.

References:

Thomas, D.B. and R.E. Fordyce. 2007. The heterothermic loophole exploited by penguins. Australian Journal of Zoology 55: 317-321.

[…] solution to this problem in ingenius: Penguins have a trick to keep this from happening. Blood vessels […]

Arctic Heat Exchange | End of Line

December 3, 2010 at 1:03 am

[…] Penguins “Cheat” to Stay Warm in Icy Waters […]

Quick Links | A Blog Around The Clock

December 19, 2010 at 11:27 pm

[…] Fossils – Paleontology, University of Otago The Evolution of Penguins, Daniel Ksepka – Penguins “Cheat” to Stay Warm in Icy Waters Klimageschichte: Das […]

Pinguine: Erfolgsmodell mit alten Wurzeln : Scienceticker – tagesaktuelle Nachrichten aus Wissenschaft und Forschung

December 21, 2010 at 8:02 pm

[…] Thus, their core body temperature stays at about 37C (about 98F), in part due to their system of counter-current heat exchangers. While the core stays warm, however, temperatures at the extremities can plunge – in effect […]

Emperor Penguin Cloaks Play a Physiological Trick | March of the Fossil Penguins

January 1, 2014 at 6:15 am

[…] I first came across the term a few years ago while reading Daniel Ksepka’s blog on fossil penguins. Most penguins swim in waters that are colder than their body temperature, and since penguins are […]

The Wonderful Net: How Camels and Penguins Are So Chill | thenaturalworldconnections

May 27, 2016 at 5:38 pm