A Tiny Fellow Joins the March of the Fossil Penguins

Early this year we reported the largest fossil penguin. This week, our team announces one of the smallest fossil penguins ever found. The new species is a bit over three million years old and represents a new species of little penguin (genus Eudyptula). We named it Eudyptula wilsonae after New Zealand ornithologist Dr Kerry-Jayne Wilson, who was an internationally respected researcher cofounder of the West Coast Penguin Trust, an organization dedicated to protecting seabirds and their habitat.

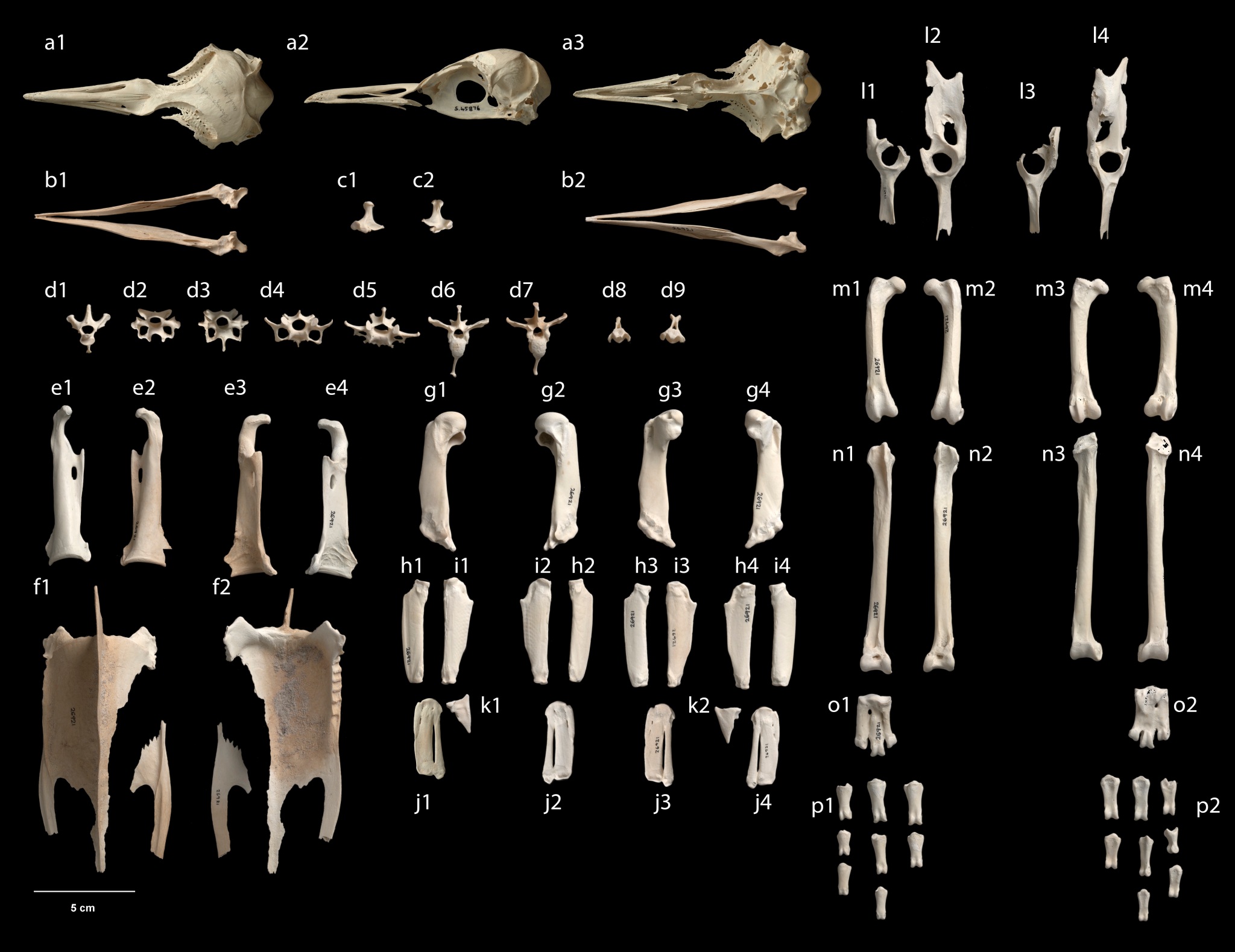

Eudyptula wilsonae is the second penguin species to be discovered in the Tangahoe Formation, which previously yielded the slender-billed crested penguin Eudyptes atatu. Most fossil penguins are known from flipper and leg bones, because these sturdy elements tend to survive the fossilization process more easily than the relatively delicate skull. Unusually, Eudyptula wilsonae is known only from the skull – two skulls but no other parts of the skeleton have been reported so far. Fossil hunter Karl Raubenheimer discovered the two skulls on the North Island of New Zealand. One skull belonged to an adult, but the other belonged to a juvenile as indicated by its smaller size and incompletely fused sutures. Both are smaller than any living penguin species, and smaller than all but one fossil species, the older and slightly tinier Eretiscus tonnii.

Eudyptula penguins are ridiculously cute. Standing about a foot tall and weighing in at two pounds, these pint-sized penguins are known for their sleek blue feathers and habit of coming ashore together in small groups known as “rafts” at dusk – an event enjoyed by sightseers at places like Oamaru and Phillip Island. Eudyptula penguins live in both New Zealand (Eudyptula minor) and Australia (considered either Eudyptula novaehollandiae or Eudyptula minor novaehollandiae), and scientists debate whether these two populations should be considered separate species or not. Individuals from New Zealand and Australia are practically impossible to tell part by eye, but their DNA suggests they have been evolving in isolation for more than a million years. Adding to the confusion, a group of Australian little penguins set up a breeding colony in New Zealand only a few hundred years ago. I personally lean towards recognizing them as separate species, but other experts on the team consider them to be subspecies.

Dr. Daniel Thomas, leader of the study, used morphometric methods to compare the juvenile and adults skulls to one another and to the skulls of modern Eudyptula penguins. The results show the new species has a more slender skull, which along with the age of the fossils suggests as a possible ancestor of modern little penguins.

Along with Eudyptes atatu and many other seabirds like the albatross Aldiomedes angustirostris, Eudyptula wilsoni helps paint a more complete picture of the seabird fauna of New Zealand in the Pliocene. This is of great interest, as the Pliocene was a warm period with higher sea level compared to the present day. Understanding what types of animals were common under these warm conditions and what type of animals were absent can help us anticipate the way species ranges may shift with increasing global warming.

Reference

Thomas, D.B., A.J.D. Tennyson, F.G. Marx and D.T. Ksepka. 2023. Pliocene fossils support a New Zealand origin for the smallest extant penguins. Journal of Paleontology doi:10.1017/jpa.2023.30

Giant Penguins Honor Giants in Science

This February, my colleagues and I published a paper in Journal of Paleontology honoring two legends in the field of penguin research. The paper describes fossils discovered in 55.5 to 59.5 million year old beach boulders in North Otago by New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Curator Alan Tennyson between 2016 and 2017. Alan found the penguin fossils on collecting trips, sometimes with help from his son Sam and expert fossil preparator Al Mannering. Al later painstakingly removed the rock to reveal the treasures inside the boulders, including nine partial penguin skeletons.

In 2018, I visited New Zealand and Alan showed me the a gigantic penguin humerus belonging to an unknown species. I was completely blown away! In fact I almost thought the bone must belong to another type of animal until I got a close look at it. In other drawers were eight more penguins specimens of varying sizes and degrees of completeness, six of which would ultimately be assigned to a second new species. Over the next few years, Alan and I worked with some great colleagues to study the penguins. Our colleague Dr. Daniel Thomas of Massey University used laser scanners to create digital models of the bones and compare them to other fossil species, flying diving birds like auks, and modern penguins. Then, in order to estimate the size of the new species, the team measured hundreds of modern penguin bones which Dr. Daniel Field of Cambridge University used to calculated a regression using flipper bone dimensions to predict weight. Dr. Tracy Heath and Dr. Will Pett of Iowa State University ran some Bayesian analyses to pinpoint the phylogenetic placement of the penguins, and Dr. Simone Giovardi, a recent PhD graduate from Daniel Thomas’s lab, contributed morphological comparisons and also created some excellent artwork.

The regression data indicated that the largest flipper bones belong to a penguin that tipped the scales at an astounding 340lbs. We named the new species Kumimanu fordycei in honor of Dr. R. Ewan Fordyce, Professor Emeritus of University of Otago. Dr. Fordyce has played an enormous role in building New Zealand’s museum collections, publishing volumes of research, and training generations of students. Although he is most well known for his work on whales, he has also collected and studied many other marine creatures including fish, a plesiosaur, pinnipeds, and of course penguins. He is a legend in our field, but also one of the most generous mentors I have ever known. Many of the fondest memories of my career are of collecting specimens with Ewan, puzzling over fossils in his lab, and enjoying his spellbinding stories. Without Ewan’s field program, we wouldn’t even know that many iconic fossil species existed, so it is only right he have his own penguin namesake.

Multiple specimens of the second penguin species were found, providing a detailed view of the skeleton. This specie weighed in at 110lbs, smaller than Kumimanu fordycei but still well above the weight of an emperor penguin.We named the species Petradyptes stonehousei. The genus name combines the Greek “petra” for rock and “dyptes” for diver, a play on the diving bird being preserved in a boulder. “stonehousei” honors the late Dr. Bernard Stonehouse (1926-2014), a pioneer in penguin biology.

Dr. Stonehouse is perhaps most famous for his 1948 expedition, during which he discovered an emperor penguin colony on the Dion Islands. His group was scheduled to be picked up by ship soon afterward, but they became stranded by pack ice and were forced to spend the winter on the islands. Dubbed The Lost Eleven” by the press, the team sheltered in tents as temperatures dropped to -40°F. Stonehouse put his misfortune to good use by becoming the first person ever to observe the full breeding cycle of the emperor penguin, a major milestone in penguin biology. As someone who needs to steel himself with hot coffee before going out to fill the bird feeder on a snowy day, all I can say is that this adventure tops any field story I know by a mile.

Bernard Stonehouse left a legacy of research and mentorship that is well remembered by many penguin biologists. I was lucky to meet him at the 2013 International Penguin Conference, where Bernard and his wife Sally asked the small group of paleontologists attending the conference to dinner. It was like being invited by royalty. I recall that he drew a small map on a napkin and one of the other paleontologists snatched it up right away as a souvenir. We corresponded afterwards and I feel fortunate to have had a chance to bounce thoughts about penguin evolution back and forth with the person we all consider the “father of modern penguin biology”.

Beside writing papers, Stonehouse wrote charming books for popular audiences. My favorite quote from his writing is:

“I have often had the impression that, to penguins, man is just another penguin – different, less predictable, occasionally violent, but tolerable company when he sits still and minds his own business.”

Over the next few days I will cover more of the science of studying fossil penguins and what we learned from the news species, but a little background on the species honorees seemed like the best place to start.

Fossil Penguins at DinoFest

Recently I was invited to be a “DinoBite” speaker at the Utah Museum of Natural History’s Polar DinoFest. The event was held virtually his year due to COVID, but on the plus side that means I can post the whole talk on this blog. Check it out if you are interested in hearing about penguin evolution – and sorry for the sound quality, I had to tape this with my laptop!

A New Fossil Crested Penguin

Apologies to fossil penguin fans, as this blog has been slow to update with new penguin paleontology news due to the arrival of the authors daughter. It’s time to dive back into the world of prehistoric penguins, and what better way to start than discussing some exquisitely well-preserved fossils from a new species! I was lucky to be part of a team led by Dr. Daniel Thomas of Massey University that studied t

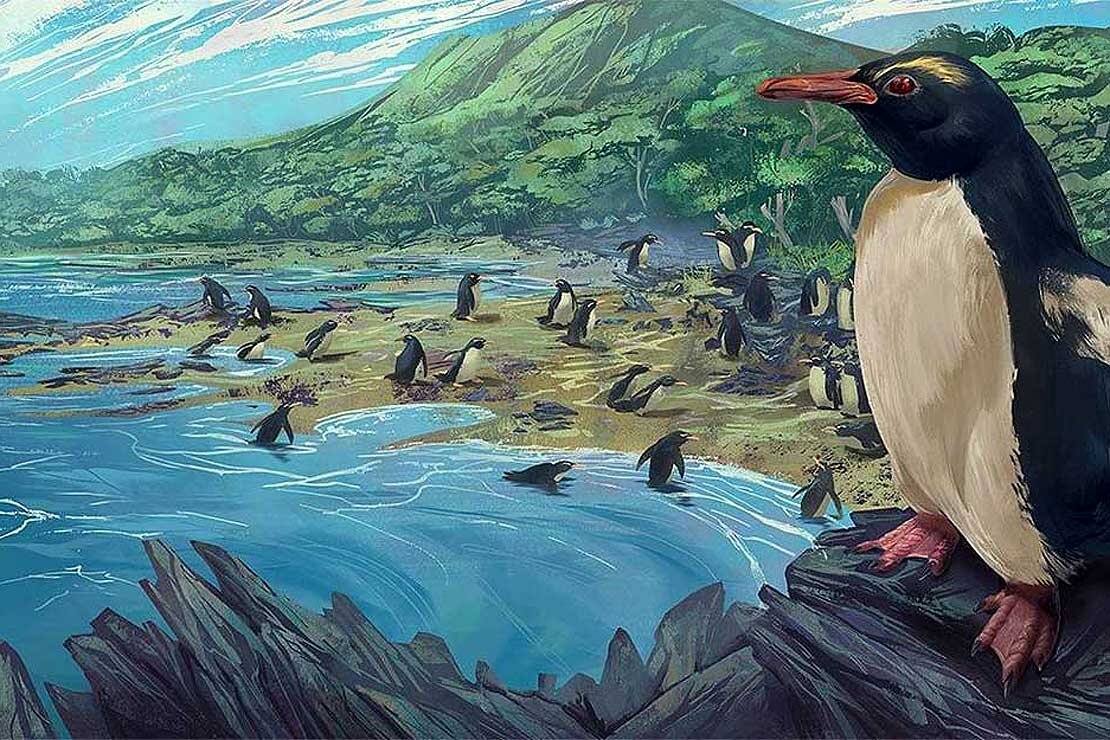

Recently, Eudyptes atatu joined the march of the fossil penguins. This species is the earliest member of the crested penguin group at just over three million years old. That’s not too terribly old compared to the 61 million year old Waimanu manneringi, but certainly ancient by human standards. Crested penguins all share golden head feathers that give them rather foppish appearances. There are between six and eight modern species of crested penguins, depending on whether the eastern rockhopper and the royal penguin are treated as full species. There are also two previously known fossil species. Eudyptes calauina is known from just a few bones from South America. Eudyptes warhami, from the Chatham Islands, has the unfortunate distinction of being the only penguin species wiped out by humans.

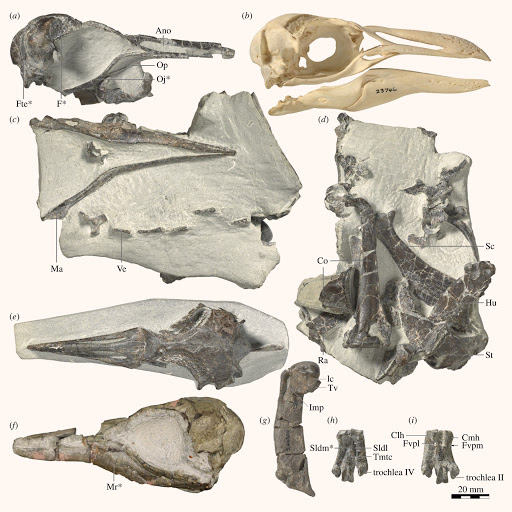

“Eudyptes” is an existing genus name meaning “good diver” in Greek. The species name “atatu” is based on the Māori “ata tū”, meaning dawn. This name recognizes that the new fossil species is the earliest member of the crested penguin group and therefore can tell us about the origins of these fantastic birds. Fossils of the species were discovered in the Taranaki region of the North Island of New Zealand and include almost every bone of the skeleton. Particularly lovely are three skulls of the species. These reveal that despite having a very similar body to modern crested penguins, Eudyptes atatu had a very slender beak. The mandible (lower jaw bone) is quite slender, as opposed to the very deep jaw bone in modern Eudyptes species. This suggests that Eudyptes atatu may have been less well-adapted to catching small shoaling prey species like krill. In living crested penguins, the tongue is very large and bristle-covered, which helps hold onto small prey snapped while swimming through swarms of krill.

The new fossils suggest the deep bill of modern Eudyptes evolved about 2-3 million years ago (very recently by geological standard). This could reflect changing conditions in the southern oceans around this same time. Beginning in the Pliocene, wind-driven upwelling of cold bottom waters transformed the oceanic food web by triggering a boom in krill biomass. The appearance of such a rich food source may have given deeper-billed penguins an advantage as they were better suited for harvesting lots of tiny prey items. A much more extreme example is scene in baleen whales, which appear to become super-sized in response to these same new feeding opportunities. Eudyptes atatu thus provides an interesting data point for interpreting big picture events as well as a neat little branch on the evolutionary tree of penguins.

Reference:

Thomas, D.B., A.J.D. Tennyson, R.P. Scofield, T.A. Heath, W. Pett, and D.T. Ksepka. 2020. Ancient crested penguin constrains timing of recruitment into seabird hotspot Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287: 20201497.

An ancient penguin skull

January 20th is Penguin Awareness Day (one of two annual penguin themed holidays, the other being World Penguin Day on April 25th). To celebrate, why not take a look at a 3D model of one of the world’s most ancient penguin skulls?

Sequiwaimanu rosieae is one of the oldest penguins ever discovered. A team led by Dr. Gerald Mayr described the species in 2018. It was found in the Waipara Greensand, just 15m about the level that yielded the current record holder, Waimanu manneringi. Indeed the genus name Sequiwaimanu means quite literally “to follow Waimanu”. The species name honors the late Rosemary (‘Rosie’) Ann Goord, the wife of the owner of the land where the fossil was collected. One of the things that makes Sequiwaimanu rosieae so important is that nearly the entire skull is preserved. Like man younger fossil penguins, Sequiwaimanu rosieae had a long, spear-like beak. This is perhaps the biggest difference between ancient penguins from the Paleogene (23-66 million years ago) and the present day. Those long beaks suggest a different style of feeding, and likely a preference for larger prey. Many Paleogene penguins reached gigantic sizes. Sequiwaimanu rosieae was about the size of a modern King Penguin, large by present-day standards but fairly moderate in size for its time.

I had the pleasure of seeing this beautiful fossil first hand about a year and a half ago on visit to New Zealand. I took lots of photographs of course but these days there are more ways to capture morphological information that standard photos. 3D surface scanning is making it increasingly easy to record and share information about fossils. the Canterbury Museum, home of the fossil, had posted 3D scans of Sequiwaimanu rosieae online so that anyone anywhere in the world can take a closer look at the fossil. Check out the link below to see the technology in action.

If you are interested in more 3D penguins, Dr. Daniel Thomas of Massey University has quite a few bird scans as well at the NZ Fauna project. Here are the wings of a Little Blue Penguin.

Reference: Mayr G, De Pietri VL, Love L, Mannering AA, & Scofield RP. 2018. A well-preserved new mid-paleocene penguin (Aves, Sphenisciformes) from the Waipara Greensand in New Zealand. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: e1398169.

Penguin Genomes Unveiled

Today, the Penguin Genome Consortium announced that they have completed genomes of all living penguin species. This international team includes research form about a dozen countries specializing in all aspects of penguin research and conservation. Project leaders Hailin Pan, Tess Cole, and Guojie Zhang invited me to contribute a fossil perspective to the paper, joining the team of 48 researchers from ten different countries who came together to complete this monumental task.

Genetic datasets can help biologists understand how species are related to one another, and how they evolved. When I started working on penguin evolution about 15 years ago, we only had data from 5 genes for penguins, providing DNA sequences that totaled a few thousand base pairs in length. The datasets were so small, I remember aligning the sequences by eye on my laptop. The complete genomes are around 1.3 BILLION base pairs long. Capturing datasets this hug were unimaginable a short time ago, but thanks to the relentless advancing of technology it is now not only feasible but affordable. It cost an estimated $300,000,000 dollars to sequence the first human genome, which was completed in 2003. Today, the cost to sequence a human genome is approximately $1000.

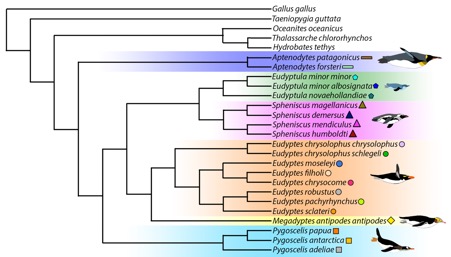

Still, analyzing datasets with billions of base pairs is a daunting endeavor. Fortunately, computer algorithms have advanced to the point where it is manageable. The team has already completed an evolutionary tree of penguins using this massive dataset, which resolves the debate over whether the Aptenodytes penguins (Kings and Emperors) are the first lineage to branch off. That turns out to be the case, meaning the biggest and most cold-adapted of the living penguins split off from the rest very early in modern penguin history (but still later than some the oddballs front he fossil record which left no living descendants).

Evolutionary tree of modern penguins based on new genomes. Figure from Pan et al. 2019.

Over the coming months, the team will use the genomes to explore what makes a penguin a penguin. All sorts of interesting analyses can be conducted with data on this scale, ranging from studies of demography (estimating the history of population sizes over time) to testing boundaries between species to understanding how things like specialized respiratory systems and scale-like feathers evolved in penguins. Understanding the history of penguins is critical because they are among the groups most highly sensitive to climate change. Several species of penguins are already declining or are predicted to decline under future climate change scenarios. It will be exciting times ahead!

Reference:

Pan et al. High-coverage genomes to elucidate the evolution of penguins. 2019. GigaSciencedoi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz117

Did Warham’s Penguin Survive into the 19th Century

Warham’s penguin / Chatham Island crested penguin. Montage of skeletal elements. Chatham Islands. Image © Te Papa by Jean-Claude Stahl. From http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz (click for original)

We recently introduced the extinct Warham’s Penguin, Eudyptes warhami. Our research team hypothesized this penguin was wiped out when humans arrived in the Chathams Archipelago over 700 years ago. There is good evidence for this, as some of the bones were found in middens (scrap heaps left behind at food preparation sites). So, we are sure that Moriori people encountered the penguins.

However, what if the penguins hung on until later colonists arrived? The British ship HMS Chatham explored the archipelago in 1791. Captain William R. Broughton claimed possession of the islands for Great Britain – no matter than people had already been living there for centuries! Captain Broughton named the islands after the First Lord of the Admiralty, John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham.

This “discovery” brought tragedy to the islands. Whalers and sealers began visiting the islands, bringing diseases. Then, in 1835 a group of nearly one thousand Māori arrived from mainland New Zealand. Soon after arriving they attacked the Moriori, killing hundreds and enslaving many of the survivors. Less than two hundred of the entire population of Moriori are believed to have survived.

By 1842, the Chatham Islands were officially annexed and made part of New Zealand and – long belatedly – the Moriori were released from slavery in 1863. By this time, Europeans had also established themselves on the islands and here we find an interesting written account of a penguin.

W.T.L. Travers read a paper to the Wellington Philosophical Society on September 11th, 1872, which is recorded in the Philosophical Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. In this paper, he reported on a number of birds collected on the Chatham Islands by his son, H.H. Travers. Many were specimens, but one was a penguin that was brought back alive. Travers (1872:221) reported: “I obtained and brought to New Zealand a live specimen of this bird, which had come ashore to moult”.

Today, no other species of crested penguins lives on the Chatham Islands, though several occur as occasionally as vagrants. Thus, Travers note about moulting is tantalizing. If the bird was moulting on the island, it may well have bred there as well. Perhaps Travers son had picked up one of the last Warham’s penguins in the world? We may never know, as the penguin is long dead and gone, and no photographs, feathers, or other remains seem to have been saved.

How did the penguin fare? Apparently it survived for several weeks without food while aboard the ship, but then took to eating fish and raw meat from the hands of its captures. By Travers (1872:221) account, the bird became quite tame around humans but was a bully to the other birds in its pen: “Though generally considered stupid, no doubt from its appearance, it was extremely cunning. When placed at night in an enclosure with some poultry it became master of the situation, its harsh cry and powerful beak striking terror into the other occupants”.

So how does the fossil evidence come into play? So far it cannot provide conclusive evidence for the age of the last Warham’s penguin as we don’t really know if any of the skeletons found so far were from the last days of the species. But, some of the fossil bones were found in deposits mixed with items like glass beads, which would have only been available from the time Europeans visited onward. However, rabbit burrows have disturbed these deposits and so it is possible older bones and younger archeological items were jumbled up together.

Can this mystery ever be resolved? I certainly hope so. Radiocarbon dating could provide evidence that some of the bones of Eudyptes warhami date to more recent times. So far, none of yielded recent dates, but there are always more fossils to be discovered.

Dwarf Yellow Eyed Penguins

On Tuesday, we met the recently extinct crested penguin Eudyptes warhami, discovered by a team studying subfossil penguin bones from the Chatham Islands. The study also turned up a “bonus” penguin. Some smaller bones collected at the sand dune sites were originally thought to belong to one of the smaller modern crested penguin species. However, mtDNA revealed something unexpected. The bones turned out to belong to a dwarf population of yellow-eyed penguin!

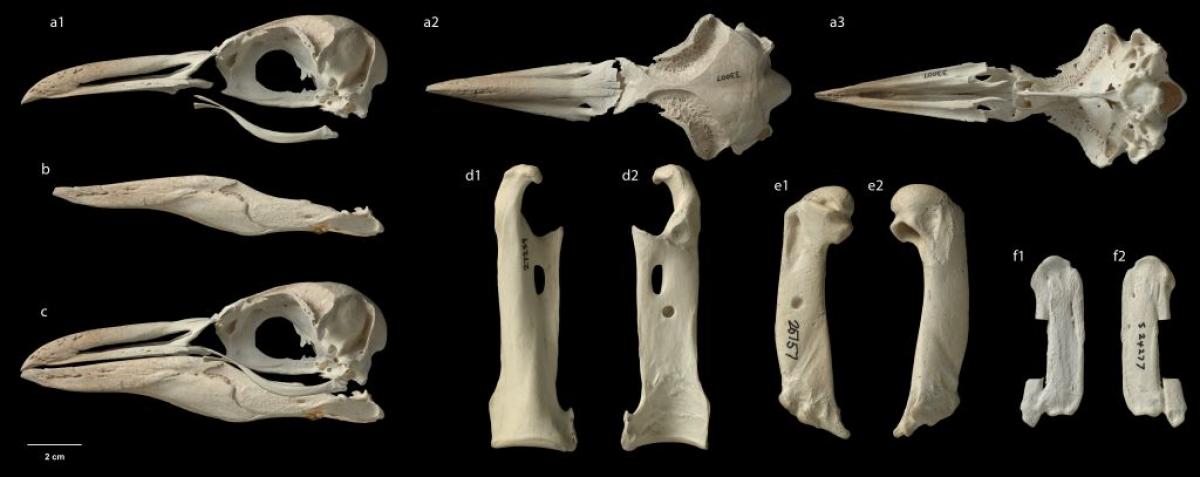

Fossil bones of Megadyptes antipodes richdalei. Photos by Jean-Claude Stahl (Te Papa).

Yellow-eyed penguins are beautiful birds. They sport a yellow face mask, and as promised by their name have a bright yellow iris. It is easy to tell a yellow-eyed penguin skull from that of a crested penguin, due to the much more slender beak of the former. Yet, the rest of their bones are very similar and it is almost impossible to differentiate a large crested penguin from a yellow-eyed penguin based on the bones of the neck, flipper, or legs. Thus it is no wonder why the Chatham Island specimens were not identified immediately: the subfossil bones were so much smaller than the modern yellow-eyed penguins that the match seemed implausible.

A Yellow-Eyed Penguin, coming ashore in Dunedin, New Zealand. Photo by Daniel Ksepka.

Eudyptes warhami showed major DNA differences with living species, indicating it was a distinct species. Our team was also able to obtain intact mtDNA from the smaller bones. In this case they showed a very close relationship to modern yellow-eyed penguins. Indeed there were far fewer differences between the mtDNA sequences of the fossil and modern yellow-eyed penguins than between the fossil and modern crested penguins. Therefore, our team considered the smaller fossils to belong to a subspecies of the living Megadyptes antipodes, which we classified as Megadyptes antipodes richdalei, in honor of the late Dr. Lance Richdale, an expert on modern yellow-eyed penguins. While the concept of a subspecies is fairly messy, this recognizes that the Chatham Island dwarf penguins would have been easy to tell apart from their mainland relatives, but had not yet fully diverged genetically. Given a few hundred thousand more years, it seems likely that Megadyptes antipodes richdalei would have continued to evolve in isolation from its mainland relatives and eventually become a fully separate species.

Together, the crested penguin and yellow-eyed penguins of the Chatham Islands tell a complex tale of how species can be wiped out. Eudyptes warhami persisted for two million years only to be snuffed out in the blink of an eye. Megadyptes antipodes richdalei reveals a different kind of tragedy — it seems to have started on its way to becoming a distinct species, but had its evolutionary journey cut short before it had the chance.

Ancient DNA Reveals Lost Penguin Species

Today, another species joins the March of the Fossil Penguins. We welcome Eudyptes warhami, an extinct crested penguin discovered on the Chatham Islands, an island archipelago about 500 miles east of mainland New Zealand.

Paleontologists have uncovered the remains of over 50 species of extinct penguins, most of them millions of years old. Eudyptes warhami is unique – it died out only a few hundred years ago, making it the youngest fossil penguin. Whereas most of the penguin species that have ever lived went extinct long before humans evolved, this species actually lived side by side with humans for a short time. Unfortunately, that brief encounter turned out to be deadly.

Composite fossil skull of Eudyptes warhami, an extinct penguin species from the Chatham Islands. Photo by Jean-Claude Stahl (Te Papa)

An international team of researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA from subfossil bones discovered in sand dunes on the Chatham Islands. I was fortunate to be a member of this team, which was led by Tess Cole, a PhD candidate at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Our study was published today in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. This project combined skeletal morphology with DNA evidence to understand how the new penguin evolved. Skeletal features provided the first clue – the existence of a lost species was hinted at by earlier comparisons of penguin bones collected from sand dunes on the Chatham Islands. Alan Tennyson (a co-author on the study) and Phillip Millener examined penguin bones from these islands, and found that they did not match up with those of any living species. DNA evidence has now confirmed those suspicions. Our team extracted mtDNA (a type of DNA that resides inside the mitochondria of cells and is inherited from the maternal line). We counted the number of nucleotide substitutions, a measure of how many mutations occurred since two species shared a common ancestor. The large number of substitutions between Eudyptes warhami and its closest living relative, Eudyptes sclateri (a living species known as the Erect-crested Penguin) confirmed that the subfossil bones belonged to a genetically distinct species. Our team named the new species Eudyptes warhami, in honor of Dr. John Warham, who carried out pioneering studies on crested penguins in New Zealand.

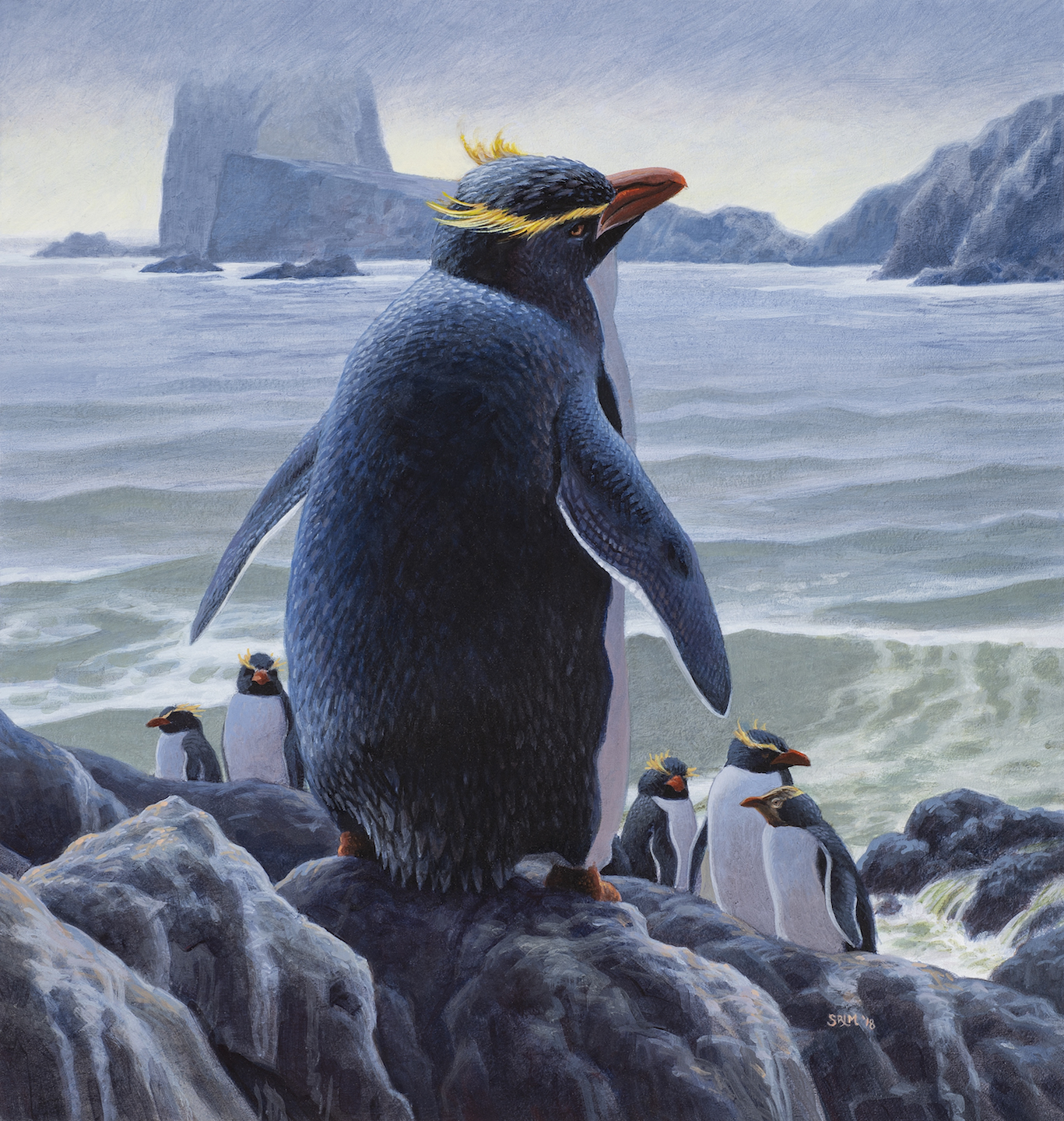

Comparisons of the bones to those of modern penguins, along with DNA evidence placing the penguin firmly within the crested penguin part of the evolutionary tree, allow us to get a clear picture of what it would have looked like. The beak was very deep like modern crested penguins, suggesting the new species was adapted to pursuing small prey including krill. Modern crested penguins have decorative yellow head plumes, and the evolutionary tree suggests Eudyptes warhami would have been no exception. Together with measurements, these details allowed Bruce Museum artist Sean Murtha to create a beautiful life reconstruction of the new species.

Life reconstruction of Eudyptes warhami. Illustration by Sean Murtha.

Aside from the pristine bone preservation and intact DNA, another nice thing about new fossils is that they are young enough for carbon isotope dating. Carbon dating provides direct age estimates for organic material, but because of the relatively short half life of the radioactive isotope carbon 14, it cannot be applied to specimens that are more than 1 million years old. Carbon dates from the penguin fossils and associated remains of other birds suggest many of the specimens were only a few thousand years old. Indeed, some of the bones were found in piles of debris left behind at human cooking sites. This provides direct evidence that the Moriori, the first people to reach the Chathams, hunted Eudyptes warhami. The penguins appear to have been wiped out shortly after the Moriori arrived in the thirteenth century. How soon is a question that still remains unresolved, and will be revisited in future posts.

Though now lost, perhaps Eudyptes warhami can serve as a warning of the need for conservation efforts. For a long time, we thought penguins escaped the wave of human-driven extinctions that wiped out birds like the dodo, which disappeared in the seventeenth century, and the Great Auk, which became extinct in the mid-nineteenth century. Finding evidence that a crested penguin perished in the human era should remind us that we need to be even more careful with the species remaining under our stewardship.

Reference:

Cole T. L. D. T. Ksepka, K.J. Mitchell, A.J.D. Tennyson, D.B. Thomas, H. Pan, G. Zhang, N.J. Rawlence, J.R. Wood, P. Bove, J.L. Bouzat, A. Cooper, S. Fiddaman, T. Hart, G. Miller, P.G. Ryan, L.D. Shepherd, J.M. Wilmshurst, J.M. Waters. 2019. Mitogenomes uncover extinct penguin taxa and reveal island formation as a key driver of speciation. Molecular Biology and Evolution.

A New Giant Penguin Weighs In

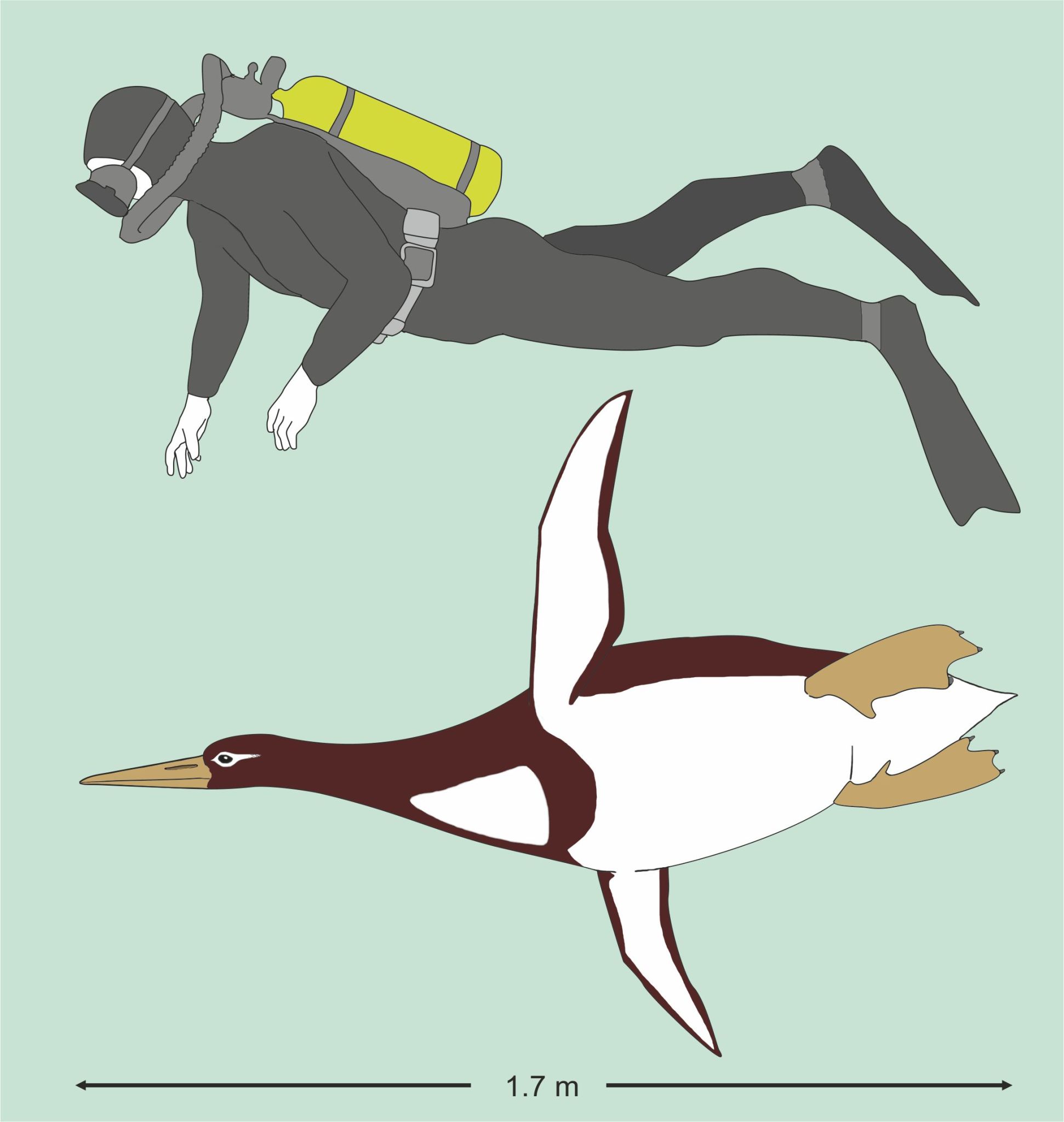

March of the Fossil Penguins is gearing up for more penguin paleontology posts. We will start with a big story from the close of 2017. A new species, Kumimanu biceae, was discovered in New Zealand. The fantastic slippered fossil tipped the scales at 101kg (over 220lbs) and lived in the Paleocene Epoch, the first time period after the extinction of the dinosaurs. The team that discovered and studied the new species named it Kumimanu biceae. The genus name refers to it being a monstrous bird: “Kumi” is a Maori name for a huge sea monster whereas, and “manu” is the Maori word for bird. The species name “biceae” is based on “Bice”, the nickname of paleontologist Alan Tennyson’s mother Beatrice.

Top row: The broken humerus (main flipper bone) of Kumimanu compared to that of Pachydyptes (another extinct giant penguin) and Aptenodytes (emperor penguin). Bottom row: The coracoids of the same three species. Both of the fossil coracoids are broken. Photo courtesy of Dr. Gerald Mayr.

What makes the fossil really cool is is the combination of ancient age and giant size. We already knew that penguins appeared very soon after the extinction of the dinosaurs, as the oldest penguin fossils are about 62 million years old. And, we already knew giant penguins existed based on tremendous fossils such as Pachdyptes ponderosus and Kairuku waitaki. Kumimanu biceae pushes the jump to giant size in penguins right back near their origin. The new fossil is between 55 and 60 million years old and also of the largest on record. That is very interesting, because it means penguins ramped up to huge sizes very quickly after losing flight. They may have been able to balloon up to grand scales quickly because of a lack of competitors in the post-extinction world, after marine reptiles like mosasaurs andplesiosaurs vanished but before marine mammals like seals and sea lions had appeared.

Artist reconstruction of Kumimanu biceae with a human scuba diver for scale. Image courtesy Dr. Gerald Mayr.

Where does Kumimanu biceae rank on the scale of penguin size? It is hard to say precisely because many individuals are known only form a single bone, but the new species is likely the second largest penguin discovered so far. The humerus (main flipper bone) is not complete, but the intact portion is almost as big as that of Pachydyptes ponderosus, a contender for the title. It is clear there was quite a bit more to the humerus before it was broken, so we can rest assured it was larger overall. More importantly, the femur (thigh bone) is huge. While the femur of Pachydyptes ponderosus remains unknown, this giant femur shows that the penguin was huge overall rather than just having a long flipper. The one penguin that may have the edge on Kumimanu biceae is Palaeeudyptes klekowskii. A massive tarsometatarsus assigned to that species is the biggest on record and suggests it belonged to an even larger penguin. However, we can’t really be sure from just one bone as different species of penguins have different proportions (e.g., some have stouter legs and longer bodies, others have long flippers and small skulls, etc.). Regardless, we can be sure giant penguin prowled the waterways of the Southern Hemisphere for a very long time.